Our analysts conducted cross-border monitoring of Russian propaganda messages in the local media outlets of Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine in their reporting on the establishment of the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Media monitoring methodology consisted of two parts: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative media monitoring identifies numerical measures or indicators that can be counted and analyzed. Qualitative media monitoring is used to assess the performance of the media against benchmarks, such as ethical or professional standards that cannot be easily quantified.

Experts in each country selected 2 TV channels and 2 online media outlets, which are among the most influential ones in covering international news and politics and have ratings figures. Our approach was also to balance pro-European and Eurosceptic, pro-government and pro-opposition media outlets for each country. Here is the lineup of media outlets we studied:

Armenia:

TV: 1st channel (Public Television of Armenia), Kentron TV

Online: news.am, lragir.am

Georgia:

TV: Rustavi 2, Imedi

Online: Ipress.ge, netgazeti.ge

Moldova:

TV: Publika TV, NTV Moldova

Online: jurnal.md, sputnik.md

Ukraine:

TV: 1+1, 112 Ukraine

Online: Pravda.com.ua, strana.ua

Each country archived the relevant media reports for the period of 1 September-30 November 2018. For TV channels, only news reports were studied, as not all talk show recordings were available in all countries. Therefore, any relevant talk shows were not taken into account in this report.

The research was carried out at the initiative of the NGO Internews-Ukraine, with the participation of Media Diversity Institute (Armenia), Journalism Resource Center (Georgia) and Independent Journalism Center (Moldova).

The Kremlin aims to spread the same narratives everywhere where they could work. Due to direct Russian interference, media affiliation or careless choice of sources, some Russian narratives about the establishment of the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church appear in all four countries.

The most widespread narrative in Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine is the one about the necessary unity of the Orthodox world in the perspective of Western intrusion. Hence, the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church is being positioned as a threat towards this unity, and one of the instruments being used by the West in its geopolitical showdown with Russia. This is another example of labelling the West an "enemy" in order to consolidate the Russians (and in this case --- pro-Russian Armenians, Moldovans and Ukrainians as well) in the face of an imaginary threat. Additionally, in all four countries articles with narratives close to messages spread by Russian propaganda also make a move against the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which is being represented as the "hand" of the West.

At the same time, Russian propaganda is very versatile and adapts to local developments in each country.

In Ukraine, the United States are being directly pointed at as the main beneficiary of the split in the Orthodox world. The topic of the Tomos (decree on autocephaly decree issued by the Ecumenical Patriarchate) was also very closely connected to local political events, especially the upcoming 2019 presidential elections.

In Georgia, the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church was often presented in the context of Georgian religious life, and the problem of the Abkhazia church's autocephaly in particular.

In Armenia, it was hinted that the Tomos will not happen as the government of Turkey made a deal with Russia and will not let the Ecumenical Patriarchate recognize the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. At the same time, Ukraine is positioned as a country collaborating with the Ecumenical Patriarchate located in Turkey, which is important in the light of tensions between Armenia and Turkey.

In all of these messages there was one red line: the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church is a dangerous development for your country (be it Armenia, Georgia or Moldova) and, therefore, it should not be supported.

Our next points will focus on the details of messaging for each country.

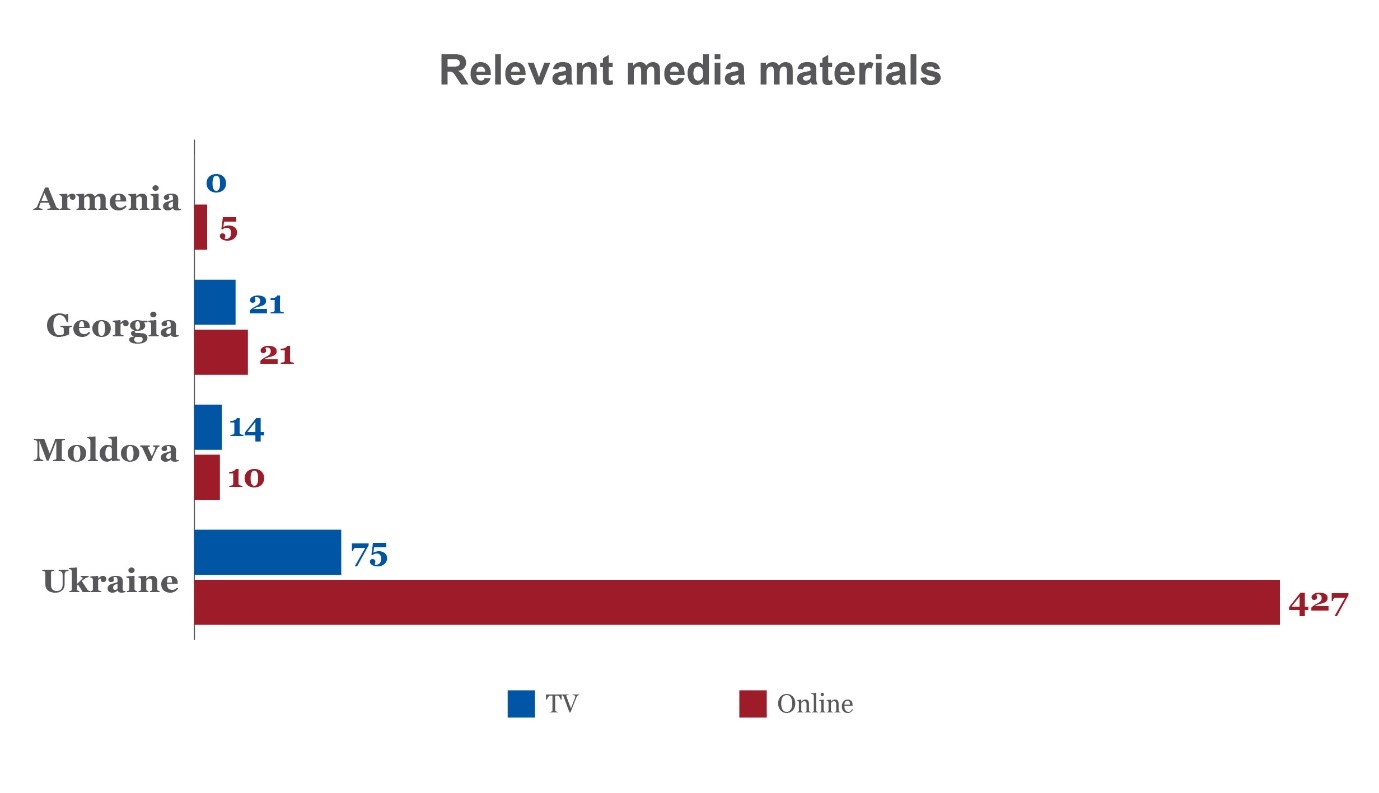

The Ukrainian media's coverage of the establishment of the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church was by far the most active. There have been 502 media reports in the Ukrainian media selected under this project regarding the Tomos for Ukraine, which is ten times more than in the Georgian media selected under this project (42 entries), which occupies second place in terms of coverage intensity. In Moldova, the topic of the autocephaly of Ukrainian Orthodox Church was covered in 24 media pieces. In Armenia, the topic saw the least coverage. Of four media outlets monitored, only one - news website Iragir.am - had at least a few reports (5 news articles).

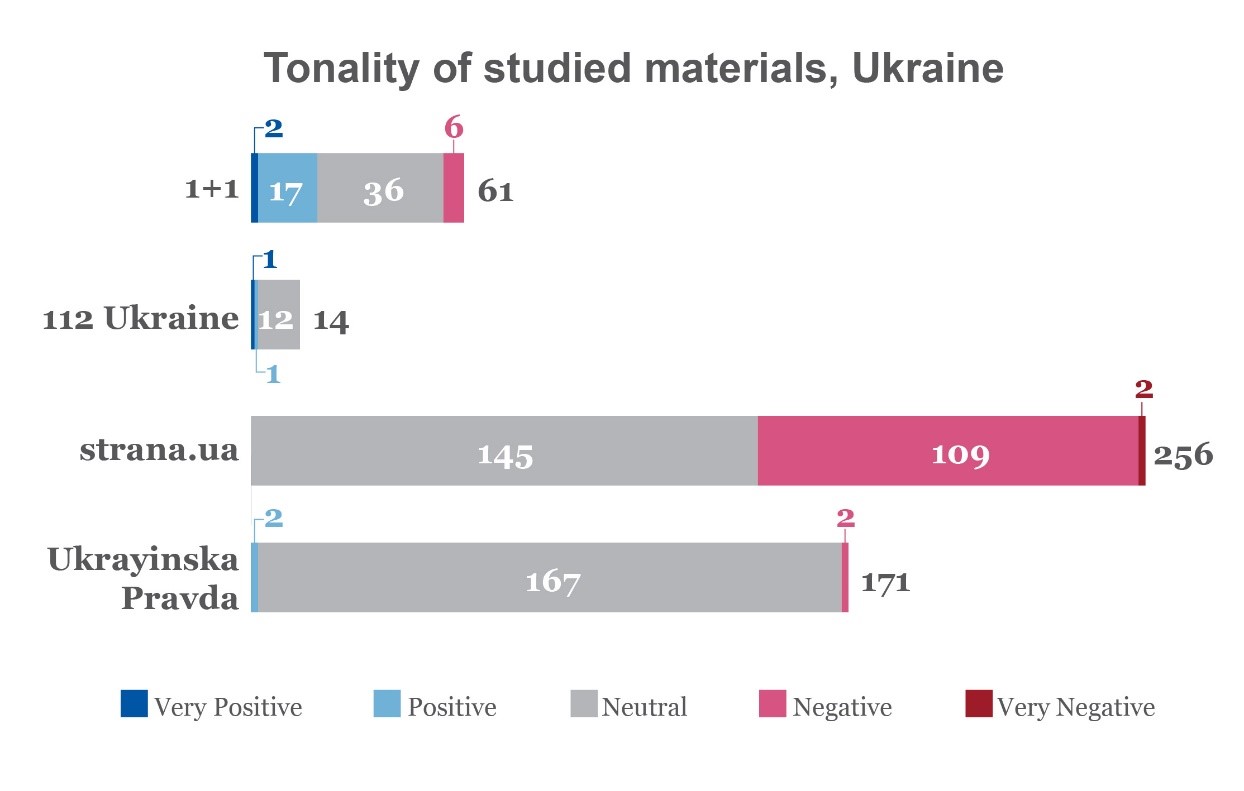

All monitored Ukrainian media outlets were mostly neutral while covering the Ukrainian Church's autocephaly. This is particularly true for TV channel 112 Ukraine (85.7% of news materials are neutral) and the site Ukrayinska Pravda (97.6% of neutral articles).

In the meantime, the TV channel 1+1 had a more positive attitude - 31.1% of media materials were positive or very positive. Strana.ua, on the other hand, had a significant share of negative posts - 43.3% of its articles were either negative or very negative.

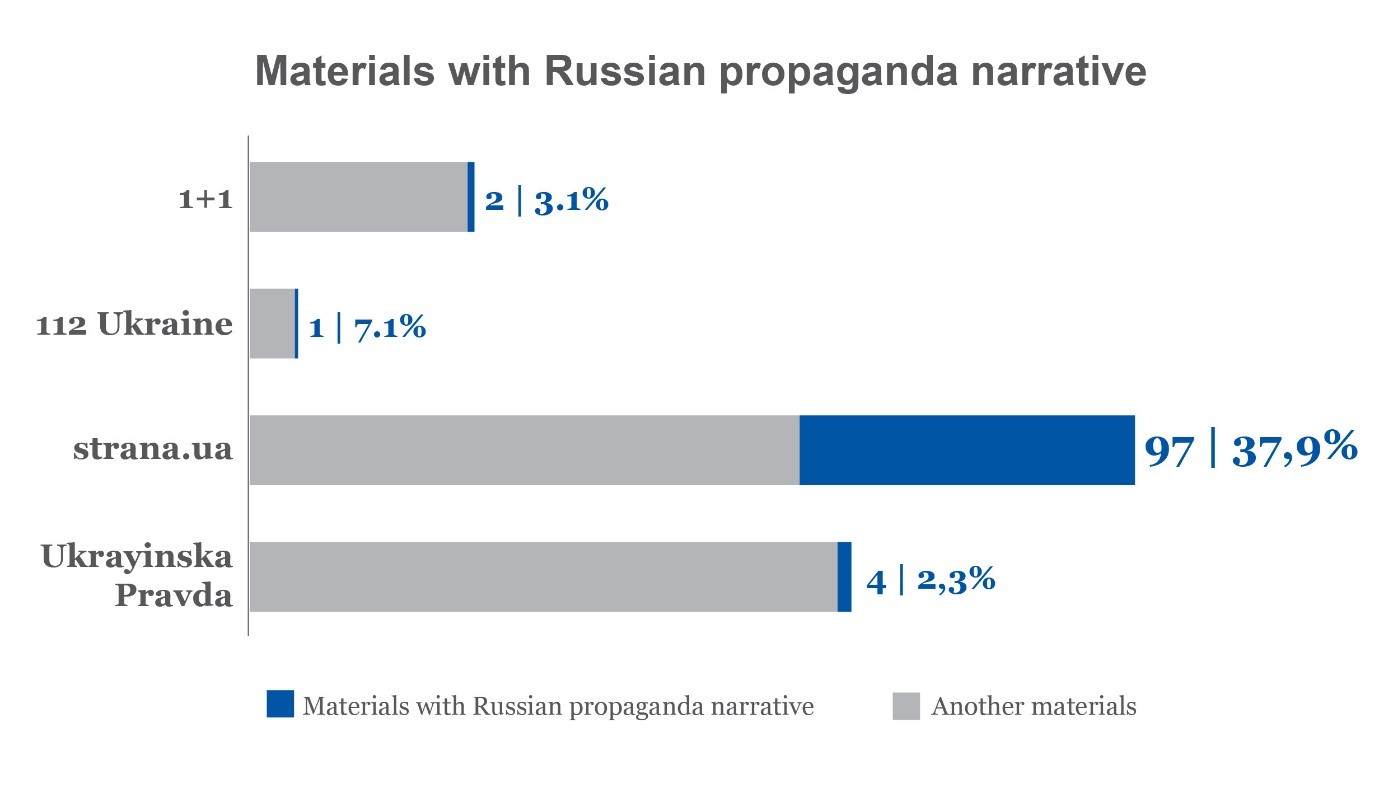

Three out of the four monitored media - 1+1, 112 Ukraine and Ukrayinska Pravda - have very few materials whose messages are close to those of Russian propaganda. However, strana.ua stands out - 37.9% of materials in this outlet are quite close to messages spread by Russian propaganda against the autocephaly of the Ukrainian church. Additionally, while 1+1, 112 Ukraine and Ukrayinska Pravda rely on such sources as the Ukrainian Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate, Ukrainian Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, Ukrainian officials and politicians, as well as the Ecumenical Patriarchate, strana.ua often uses sources from the Ukrainian Church of the Moscow Patriarchate or the Russian Orthodox Church, as well as Ukrainian opposition politicians, all of which are biased against the Tomos. strana.ua also calls the Ecumenical Patriarchate the "Istanbul Patriarchate" in order not to highlight its superiority over the Moscow Patriarchate.

Here are the most widespread narrativesclose to those spread by Russian propaganda:

● The Tomos may not even be granted to Ukraine;

● If the Ukrainian church receives the Tomos, it will initiate a split in world Orthodoxy;

● After receipt of autocephaly, the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra and other church buildings will be taken away from the Moscow Patriarchate. In this case, Ukraine will face a civil conflict on religious grounds;

● Ukraine is a canonical territory of the Russian Orthodox Church;

● Constantinople is preparing not to give Ukraine autocephaly, but to establish an exarchate --- that is, a branch of the Ecumenical Patriarchate;

● The Turkey-based Ecumenical Patriarchate cannot rule the Orthodox churches, because Turkey is a Muslim state, not an Orthodox one;

● If Ukraine held a referendum on the Tomos, it would not receive support;

● The United States rules political and religious life in Ukraine;

● Poroshenko bribed Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew to ensure granting of the Tomos;

● In Ukraine, the authorities, President Petro Poroshenko in particular, began persecuting priests belonging to the Moscow Patriarchate;

● In Ukraine, Christianity is forcibly imposed by nationalists. The Tomos is a key to this.

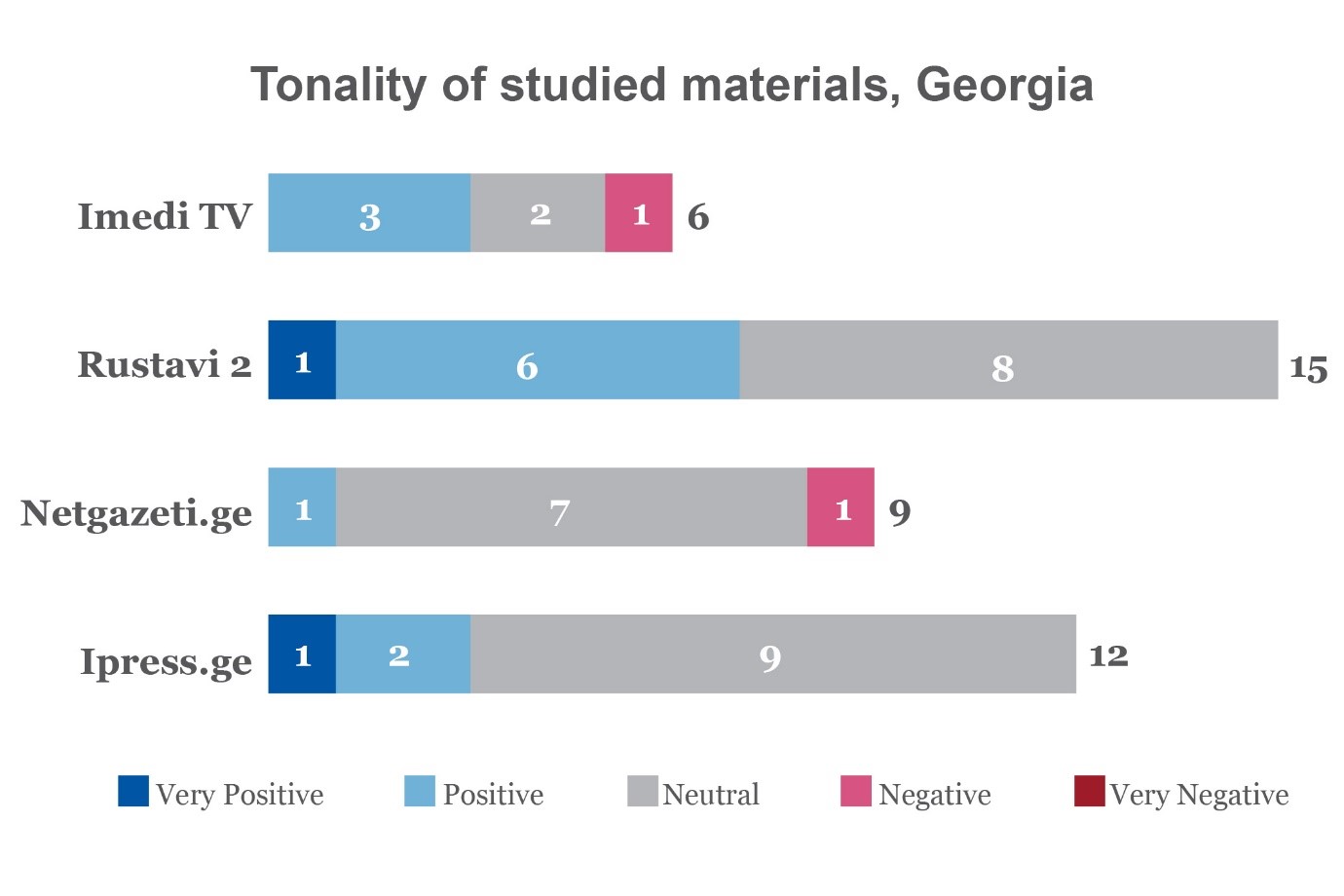

Imedi TV (the pro-government TV channel) had the example of critical coverage of the Tomos, although positive messages on the topic prevailed; Rustavi 2 (the pro-opposition TV channel) did not contain critical coverage, and positive coverage was twice as big as on Imedi TV.

Another example of divergence is that both channels engage completely different experts. For the purposes of analyzing the issues, Rustavi 2 relies on theologians clearly positive towards Ukrainian autocephaly, and also critical of the Georgian Patriarchate, while Imedi TV relies on those theologians who are more or less positive about Ukrainian autocephaly, though note some caution should be shown.

Georgian online media outlets cover the issue more impartially, in-depth and consistently than TV companies. They offer both news and analytical articles to their audiences, including expert opinions. They also inform the audience about the topics missed by TV media.

On both Georgian TV channels, there are cases of repetition of the Russian narratives on the establishment of the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Both media broadcast such information in a neutral way, but it was balanced by opposing views provided by these channels. However, such content is relatively minor compared to general coverage on the issue of the Ukrainian Church's autocephaly. Russian propaganda narratives also get into monitored online media indirectly, even though online media outlets try to respond to the messages spread by the Russian media.

Here are the main propaganda narratives found in the Georgian media:

● The Ecumenical Patriarchate is a slave to the West and is being used to split the Orthodox Christianity;

● the declaration of Ukrainian autocephaly makes recognition of the autocephaly of such churches as the Abkhazian one unavoidable;

● recognition of Abkhazia's autocephaly by Russia will be a forced step, as a result of the split of the Orthodox Church by the West;

● recognition of Ukrainian autocephaly by Georgia will make the process of recognition of the autocephaly of Abkhazia and final separation from the Georgian Patriarchate irreversible.

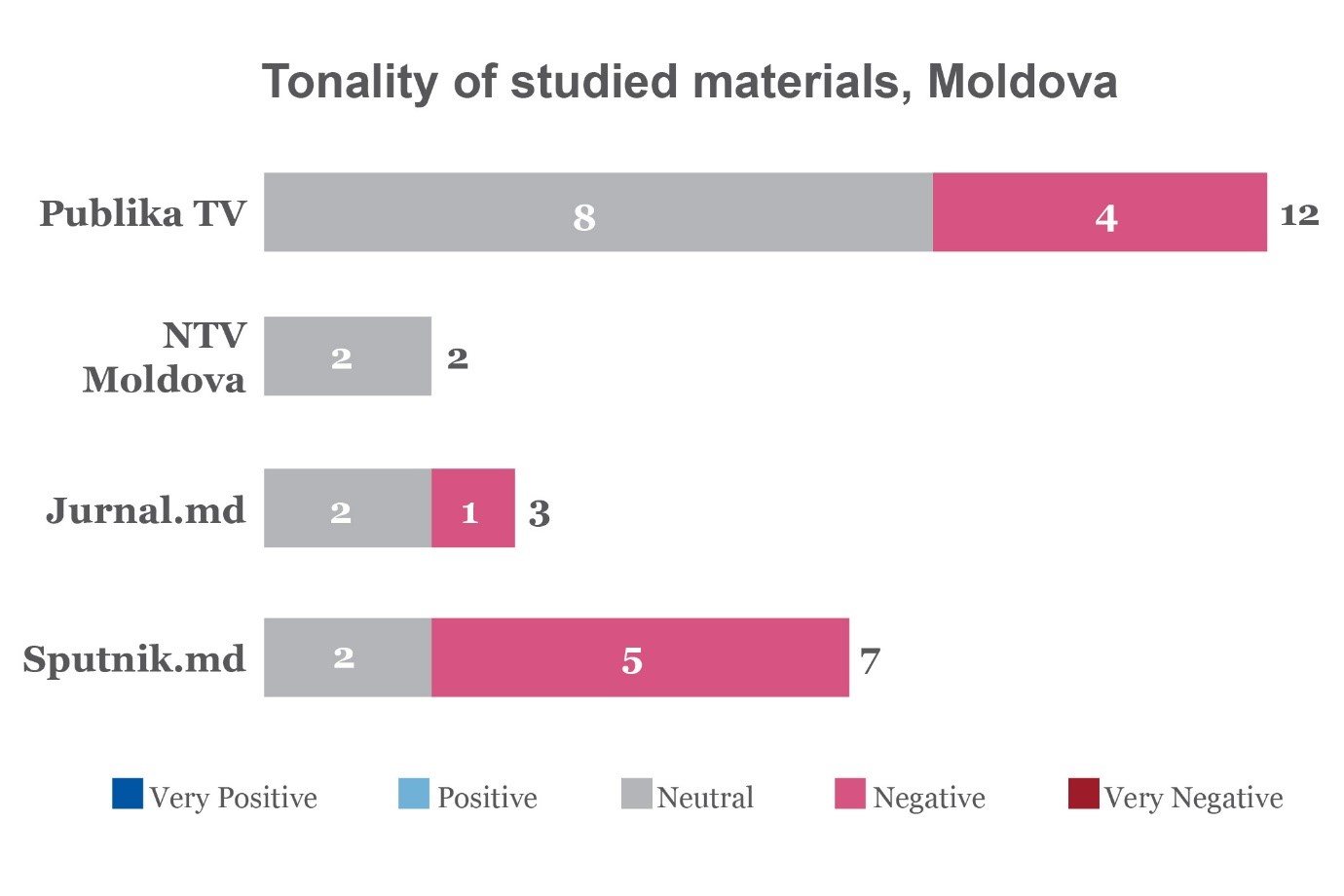

In three out of four monitored Moldovan media - Publika TV, NTV Moldova and Jurnal.md - most reports were short pieces that presented limited information on the topic, usually quoting one source of information. Consequently, most reports lacked clarity. The background information provided was not enough to understand the problem clearly. Most reports informed about the current development of the situation, without presenting historical background or giving a plurality of opinions.

On the contrary, in Russia-controlled outlet Sputnik.md, most reports were large stories that provided detailed background information on the controversy surrounding the Tomos. The tone of coverage was mostly biased, positive towards Russian Patriarchy and negative with regard to the Kyiv Patriarchy. Sources quoted were transparent (i.e. could be identified) but not diverse, in most cases representing opinions opposed to autocephaly.

NTV Moldova, which broadcasts local content and rebroadcasts content produced in Russia, covered the issue of Ukrainian Church autocephaly irregularly in 2 news reports. The fact that NTV Moldova omitted to cover this issue may indicate a case of manipulation through omission.

Meanwhile, Sputnik.md spread the message that the Ukrainian Church attempted to divide Orthodox Christianity, and that it was schismatic. Sputnik also informed the Moldovan orthodox faithful on how to proceed further after the Russian Church announced that it has ended its relationship with the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.

Here are the main propaganda narratives found in Moldovan media:

● Ukraine's "regime" acts against its own people and intervenes in the religious life of Ukrainians;

● The Orthodox world should be unified at any cost;

● If the Ukrainian church receives the Tomos, it would initiate a split in Orthodoxy;

● Patriarch Filaret is a schismatic who has been trying to split Orthodoxy.

Out of the four studied Armenian media, only one (online news site lragir.am) was seen to have posted publications related to the topic of the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church during the reference period. This media outlet published five articles on the topic in September-November 2018. It is worth noting that in the further months selected for study, the media never returned to covering the Tomos.

The monitoring enabled the conclusion to be drawn that it was not just the Tomos, but also developments taking place on the majority of post-Soviet territory, including Ukraine, that failed to spark interest in Armenian media. Overall, Armenian media relatively rarely cover events on the territory of the former USSR, except for Azerbaijan (the country Armenia is in conflict with) and partially Russia (with which Armenia maintains the most intensive connections in various areas), as well as Georgia (a border state used by Armenia and its citizens for most of their land communications with the outside world). Additionally, it was a period of time when the interest of the Armenian public was focused on their own problems and events - the aftermath of the "velvet revolution" and situation on the contact line of the Karabakh conflict and at the Armenia-Azerbaijan border.

All five available publications failed to mention the Ukrainian side of the controversy, the positions of other Orthodox churches, besides the Russian church, and parallels between the issue of the Tomos and the newly-acquired autocephaly of the North Macedonian Orthodox Church, etc.

Though the language of the publications was quite politically correct, some of the conclusions were definitely not. In particular, one of the articles contained an opinionated statement that the Turkish authorities have decisive influence over the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Apart from discussing the consequences of the Tomos, the news site quoted only Russian officials and politicians, including "predictions" made by LDPR leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky about "bloody clashes" in Ukraine.

Therefore, for Iragir.am, the biggest interest lay in the consequences of the Tomos for Russia and the connection between its loss of influence on the international stage as a state and its church, as the one striving for leadership in the Orthodox world.

Here are the main propaganda narratives found in Armenian media:

● The Tomos will not happen as the government of Turkey made a deal with Russia and will not let the Ecumenical Church recognize the autocephaly of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church;

● The Tomos is deliberate reinforcement, legitimization of the schism within the Ukrainian Orthodox Church;

● The Tomos is a mistaken decision by the Ecumencial Patriarchate that needs to be changed if it wants to restore ties with the Russian Orthodox Church;

● The Tomos is part of the process of crushing the concept of "the Russian World" and ideological grounds of Russian expansion.

Russian efforts can be countered if national governments, media outlets and civil society in Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine work together. Here are the necessary steps:

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Internews Ukraine and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

The project benefits from support through the EaP Civil Society Forum Re-granting Scheme (FSTP) and is funded by the European Union as part of its support to civil society in the region. Within its Re-granting Scheme, the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum (EaP CSF) supports projects of its members that contribute to achieving the mission and objectives of the Forum.

Grants are available for CSOs from the Eastern Partnership and EU countries. Key areas of support are democracy and human rights, economic integration, environment and energy, contacts between people, social and labour policies.